An increasing amount of social interaction takes place online, whether in public or private spaces, and using digital technology. This has resulted in changes to social practices, the formation of communities, and relationships to place. These changes bring challenges for social research but also opportunities that complement established methods.

Netnography

- Conducted in online spaces.

- Although these are ‘public spaces’, it is still important to make the research presence and intentions apparent to community members and obtain relevant consent.

- Time commitment will vary. The material may be relatively quick to access but, as in offline methods, the development of relationships and understanding takes time, as does analysis of material.

The term “netnography” refers to online or internet ethnography, engaging with communities in virtual spaces, such as those on the social media platforms Facebook or Instagram. By participating in a group and posting content, the researcher is making an intervention in the community, akin to asking a question in an offline discussion. Depending on how an online group is set up, spaces may be open/public or closed (requiring administrator approval to join and post content).

Although internet-mediated research does not take place in-person, many of the same ethical considerations apply to online as in offline interactions.

- It cannot be assumed that participants have an expectation of the ‘public’ nature of online information. As at a physical site, notices can be posted (on pages or in groups) informing people about the research.

- You will need to consider consent procedures and issues of anonymity.

- A search of online platforms and websites using key words and hash tags identified potential groups, which were looked at in terms of size of membership, levels of activity etc. Some groups were closed, so it was not possible to see content without requesting membership. In other cases, posts were public but posting and commenting was limited to members only.

- There were no sites or pages dedicated specifically to the Hood Stones, so the research focused on communities with an interest in H.M.S. Hood. The largest and most relevant online group was a Facebook group run by members of the H.M.S. Hood Association.

- The next step (the same whether a public or closed group) was to contact the group admin to explain the research focus and obtain consent. Contact had already been made with the H.M.S. Hood Association, who were interested in the research proceeding.

- Membership confirmed/Admin consent received, it is possible to post to the group about the research – in this study the first post was about an upcoming site visit.

- Subsequent posts during and after the visit provided information/images and asked questions. Each post included the research information (being able to link to a website with additional information about the research was helpful in this context).

- In addition to public posts, some more active contacts were contacted directly on messenger to request more detailed information or to set up semi-structured interviews.

- Responses were always given to comments or questions directed back about the research.

- In addition to the real-time conversations, it was possible to search the group for previous posts that mentioned the Stones. These posts and the comments or reactions that they generated were included in the analysis.

- The engagement was combined with online observation – monitoring other public ‘participatory media’ platforms for posts and images related to the Stones.

- For many communities, including communities of location, online engagement forms an important part of their communication.

- There are connections between the activities and discussions taking place online and offline, but online engagement is not a simple mirror of offline relationships and activities.

- Social media platforms are used differently by different communities, in some cases fulfilling unique functions that do not have offline equivalents.

- Online engagement can be a practical method for reaching potential participants, particularly if you anticipate there will be a geographically dispersed community of interest, as in the Hood Stones case.

- Although online platforms may be quick to access, establishing relationships of trust, understanding group dynamics, and contextualising posts and comments, takes time and care.

- Direct message conversations with some group members and offline interviews with others brought wider understanding of how the online group functioned and the detail behind some of the posts.

- The majority of the online discussion/content is generated by a relatively small number of people, with likes or occasional questions/comments from others.

- Engaging the wider community online was more difficult than anticipated, although posts with images and/or news seemed to generate more response than a direct enquiry. Visiting a site and having information or photos to share is therefore extremely useful for online engagement.

- The online discussions also helped provide wider context to sites and how they currently feature as compared to other topics and sites or objects of significance.

- Being able to refer potential participants to online information about the research was also helpful and in keeping with the community’s own means of communication.

Photography/videography (by participants)

- May be accompanied or unaccompanied, linked to diaries or a stand-alone activity.

- Can be conducted with multiple individuals or as a group exercise.

- Time commitment from researcher 3-6 hours, assuming two to three meetings to set up the exercise and discuss the resulting images. Time commitment from participant may exceed this and vary depending on the approach taken.

As digital technology becomes more affordable, an increasing number of people are engaging in photography and videography using cameras and their phones. Hand-held devices that can be connected to the internet, allowing for instant expression and response, are for many people an easy and accessible means to interact with their wider community or group of friends. Ethnographic researchers have embraced these new forms of cultural production, representation and creativity, both as subjects for study and as part of the research process. Methods such as photo diaries can provide a way of bringing otherwise excluded groups into a project.

Note: use of non-digital, disposable film cameras offers the opportunity to review all a participant’s images, rather than a sample they have selected. Providing the materials for the activity also addresses potential barriers to participation. Where a selection is made the reasons for selecting or discarding images can also be revealing.

Based on the Cables Wynd House study, where a photo-elicitation exercise was conducted with a pre-existing photography group, identified through notices posted in a local community hall. Each of the meetings with the group lasted 1-2 hours.

- Contact was first made via email with the activity co-ordinator and the group leader to explain about the research.

- This was followed by an initial meeting with the group at one of their regular sessions, to explain about the research and request their participation in the proposed activity. As it happened, they were looking for a site to go to for their next fieldtrip, so they agreed to focus on the House and surrounding area.

- The following week the 5 members of the group that were interested to participate met up with the researcher to walk together to the site, visiting the interior of the House as a group, before exploring the area individually and reconvening.

- In the final meeting, which was attended by a couple of group members who had not participated previously, each of the photographers shared 10 of their images which were discussed by the group. This meeting was audio recorded to complement note taking.

- Notes and analysis focused on the photos chosen and the way they were described/motivated for/discussed.

- With participant permission, a selection of the photos were used to create a display in the vestibule of the building. The images were used as prompts in discussions with people at the House and a comments sheet was left up for the duration of the exhibit (1 week), but this was removed during the intervening period.

- Images of the display were shared back with the photo group members together with some of the responses received.

- The activity was not undertaken principally in order to analyse the resulting images, but to prompt group discussion on aspects of significance and associations with the site and in this regard it proved very successful.

- The discussion took place during the third meeting, by which time participants had a degree of familiarity with the researcher, as well as having had a shared experience of place during the site visit. This resulted in a free-flowing discussion, requiring minimal facilitation.

- The sharing of the photos prompted detailed discussions of location and personal or family connections to the area. Participants who had initially indicated that they had only passing familiarity with Cables Wynd House shared knowledge of the area and, in some cases, of the House as well.

- The interaction between group members on the images revealed different values or associations. Viewing one another’s photos began to open up more reflective discussion.

- During the photo group discussion, the photographer was there to explain the intention behind their image and the experience connected to it. Respondents not only spoke about what was in the pictures but also how places had changed, past experiences and absences, constructing a narrative based not only on what the picture showed.

- When the images were used in the photo exhibit, they were left completely open to interpretation. The context of production and image content was not necessarily significant in how the images were used by respondents who used them to create narratives based on their own knowledge and experiences.

- In both situations, with the image producers and with other respondents, the photographs proved a useful hook for discussions. Films and images were also used in creative methods as a means to initiate discussion.

The Plural Heritages of Istanbul project has produced a toolkit (number 6) on Community Co-production that includes sections on film, photography and audio methods.

Virtual depictions & 3D models

- A group activity – meetings and on-site activities.

- Some basic training and access to specific equipment (or software) required.

- Time commitment will vary.

Identification of the object or feature that is the focus for the scanning, manipulating the virtual version, as well as reflections on the 3D model, all offer insights into the values associated with the original site.

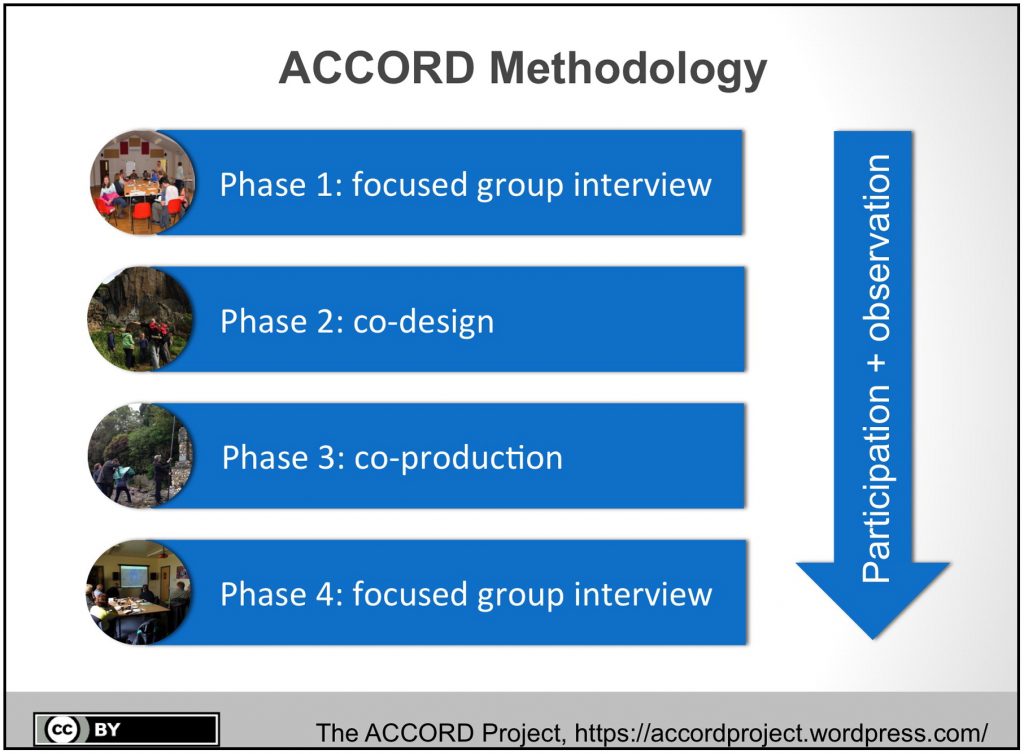

This method was successfully trialled in the ACCORD project (project information available here) as a collaborative activity with groups of 6-12 people:

- Group members identified significant aspects or objects to focus on.

- Digital scanning or photogrammetry (a composite of digital images) was used to create a virtual depiction that can then be digitally annotated and shared.

- Focus group meetings before and after the site selection and creation of the models, as well as discussions through the process, allowed the researchers to explore questions of value and authenticity with participants.

- In some cases, after creating a virtual version, a 3D model of the feature or object can be printed and used in discussions.

Reflections on the methodology are also included in this article by Jones, S. et. al. (2017) 3D heritage visualisation and the negotiation of authenticity: the ACCORD project, which includes the below diagram:

Although it was not possible to trial either virtual depictions or 3D models in the case studies, the reasons why provide some useful points for consideration:

- Engagement early-on with the collections managers is necessary when working with objects (for photography/scanning or any type of engagement), as there may be requirements for access that have to be taken into account in the design of the activity.

- Where will the activity take place? It may not be possible to take objects off-site (e.g. to a community location), either at all or without a conservator present.

- Are the relevant skills, time, and equipment available to facilitate the exercise?

- What are the implications for the duration of engagement (e.g. if access to objects requires approval or image processing/3D printing needs to take place elsewhere/takes time)?

- How unique are the objects in the collections? Are there other examples (or replicas) of these objects that can be used for the purposes of the discussion?

A selection of virtual depictions can be seen on Sketchfab, https://sketchfab.com/ (see the Cultural Heritage & History section). Once the virtual depiction exists, it could potentially be annotated, as in a participatory mapping exercise, or used in other discussions, as with digital images.